Amalgamating art and science, the multimedia installations of German artist Verena Friedrich use analog and digital technology to offer experiences that often involve organic forms. The artist builds machines equipped with complex devices that she adjusts like sensitive instruments, programming the components and assembling the electronic parts with great precision. Friedrich’s practice can be characterized by a continuous movement between working in the laboratory, collaborating with scientists, and conducting empirical experiments in the studio. In a text about the installation TRANSDUCERS (2009), she describes her work as “freely oscillating between life and laboratory work, between individuality and serialization, between biology and its technoscientifical appropriation.” (1)

TRANSDUCERS (photo: Max Schroeder)

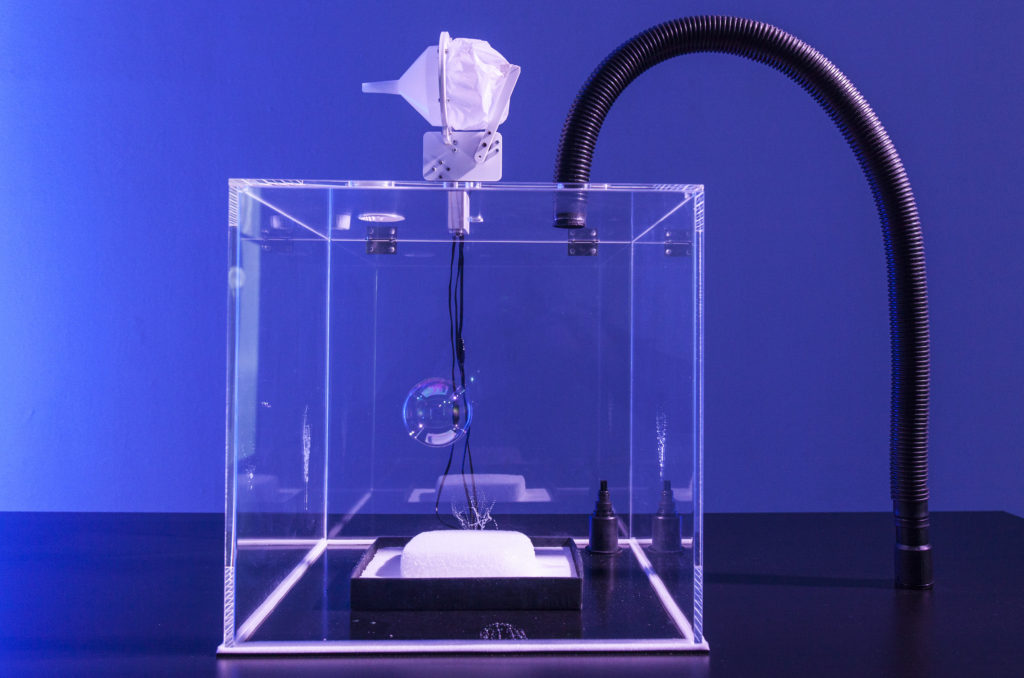

VANITAS MACHINE (photo: Miha Fras)

Borrowing the pared-down aesthetic of the sciences and making use of the transparent aspect of a glass bell and a Plexiglas cube, the kinetic works VANITAS MACHINE (2013) and THE LONG NOW (2015) allegorically reflect on the aging process and longevity. An integral part of Friedrich’s research is an extensive study of iconography. The two works express an ephemeral materiality, the passage of time, and the fragility of life through vanitas—a genre historically associated with still life and portraiture in painting. The flickering flame of the candle in VANITAS MACHINE echoes George de la Tour’s painting Magdalene with the Smoking Flame (1630–35), depicting a woman seated before a candle and holding a skull, the typical symbols of vanity. Friedrich’s installation prolongs the lifespan of a candle for as long as possible by controlling the environment in which the blame burns.

THE LONG NOW (photo: Victor S. Brigola)

Time has always been an inherent and integral element of kinetic art. In THE LONG NOW, created in Montreal during a residency at OBORO and PERTE DE SIGNAL’s RUSTINES | LAB in spring 2015, the duration is in relation to the expectation created by the formation of a soap bubble: the machine produces a perfect sphere, whose membrane is made from a soap and glycerin solution. In Bubbles, German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk describes the joy of blowing soap bubbles, as well as the expectation and hope surrounding the concept of these “shimmering entities,” (2) which he also calls “globes.” The bubble motif stands for death, evoking evanescence and impermanence. Inside a hermetically sealed prism, a bubble floats for a period of time before it bursts. The artist conducted experiments to test the gravity and other physical and chemical phenomena in order to create optimal atmospheric conditions inside the cube. The work contrasts with David Medalla’s extravagant bubble machines, Cloud Canyons—produced in several versions in the 1960s—which self-generate copious jets of foam. British art critic and curator Guy Brett has emphasized the freedom of movement that sculpture can have by considering it as a “…machine whose forms should be beyond its immediate control.” (3)

Demonstrating harmony between organic and technological forms, VANITAS MACHINE and THE LONG NOW slowly unfold and expand. Precisely and rigorously controlled, these machines keep viewers in suspense, reminding them of the fragility of life through the delicate texture of a candle flame and a bubble. While science and technology are constantly working to accelerate the pace of daily life, even striving to intervene in the aging process, these works emit an unfathomable calm.

Text: Esther Bourdages

Translated from French by Oana Avasilichioaei

Header pic: Anne Parisien

(1) Verena Friedrich, http://heavythinking.org/transducers-2009/, accessed on August 7, 2017.

(2) Peter Sloterdijk, Bubbles: Spheres Volume 1: Microspherology, trans. Wieland Hoban (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2011), 18.

(3) Guy Brett, “Le cinétisme et la tradition en peinture et en sculpture,” Artstudio 22 (1991): 87. (Our translation)